Letting go

40 Years ago, my youngest brother Paul fainted while on-campus where he was only just beginning his journey as a college freshman. That day changed our family’s perception of life and it’s fragility forever. As you might imagine, the years that followed felt like an endless roller-coaster for Paul, my parents and my siblings as we all worked to navigate our emotions and the oncological system as it was. Ultimately, my brother was presented with a “no hope,” diagnosis, words unfathomable for any family.

My parents and brother went on to face his palliative surgery in the Midwest. (If you’re unfamiliar with what Palliative Care is, it’s a medical approach meant to preserve time and improve the patients’ quality of life.) Needless to say, when my parents - present after the procedure - heard the words “successful surgery,” it truly held no solace for them.

The exact chronology has become a bit hazy, but what unfolded was a series of events that included bearing witness to catatonia, weakness, pain, distress, fear of the unknown, lonely hospitalizations as well as a progressive series of “lasts.”

We didn’t know where to turn and when we needed guidance the most, we were alone. There were no offers of assistance, no social workings, no support outside of our immediate family. I can still recall one night where we truly felt it was my brother’s last, as the pain in his head was unrelenting and the Morphine that my sister had taught us to administer felt as though it was taking a lifetime to work. We were lost, huddled together in the next room plugging our ears, crying, frightened, oblivious as to how else we could help. We longed for a tender touch and a guiding hand. It felt like an eternity before Paul was able to get out of bed and walk down the hall, calling our names and using the facilities, spared- another resurrection.

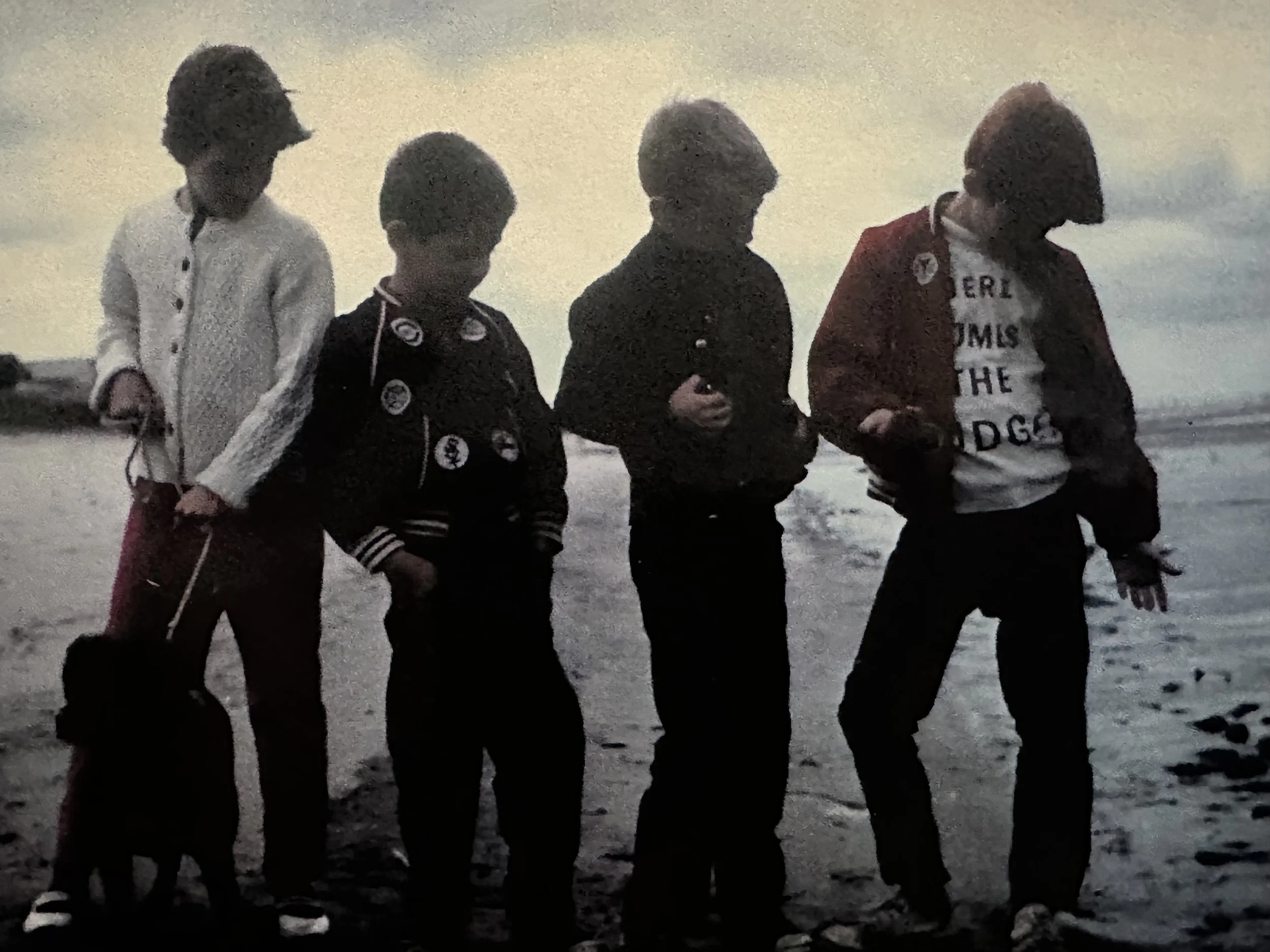

During Paul’s final week, we traveled to Cape May, New Jersey, our childhood playground. There we experienced other ‘lasts’ - some we’d cherish forever like playing on the beach, playing miniature golf, and going to the arcade, while others became painfully unforgettable, like watching our father carry his youngest son back to the home we were renting, as he was too weak to walk.

There were conversations at that time about ways to make breathing easier, pain less, food more palatable, and ultimately which way to drive home so that we would be sure to hit all the memorable spots. We clung to those memories from all those rides over the years, taking the exact same route, spooky houses with doll heads in the windows, the restaurant where we would stop to get a “coke in the bottle,” with two straws to share and many more.

In the end, there was Paul at home in his room sending my mother down to get him his beloved apple juice as my father pulled out of the driveway. He was heading off to friends to return a stationary bike for which there was no further use.

My Mother returned to see her baby boy transitioned. My mother, unsuspecting and all alone, began banging on the window hoping to catch my father’s attention. She had to call his destination to relay to their friends the unspeakable, having to contact the doctor while all alone in the house with her child. No one to comfort, no one to assist, no one to enlighten us about what may lie ahead.

Clearly, we navigated this as best we could.

It would have been a welcome relief to have had some understanding of what was going on and what may lie ahead. We could have used some support to provide a calm presence and clarity. Our family did our best to make sense of this transition which was natural, but to us, an unnatural process. We needed a resource, a hand to squeeze, someone to hold, to prepare us for an event for which you can never be ready. Having someone may have made a difference not only in the moment, but also with our grieving process going forward.

We all had our conversations with Paul- always conscious of needing to exude hope. We had what felt like stolen moments, reading books to him during hospitalizations, sneaking in after visiting hours. Our parents picking up the pieces when someone unknowingly shattered his dreams. EOL Doula’s (End of life Doulas) are present for this purpose, to provide a knowing presence, someone who sees you and stands by you during these times. An EOL Doula is someone who has the information that could have steadied our feet a bit.

In the aftermath of Paul’s death, our family struggled with grief, not knowing what was “normal,” and not realizing that grief was unavoidable and so different for each of us.

End of Life Doulas specialize in guiding relatives, families and significant others through this phase of life all the while being present, listening and assisting or completing tasks required by those transitioning. Doulas are experienced caregivers who provide the help requested to those who may not have the reserves to see them to completion. They create a foundation for grief, a starting line if you will, adding clarity and normalcy to the process.

Doulas provide a steady shoulder to support those dying, and once our loved ones are gone an End-of-Life Doula is there for the bereaved supporting us along the way.

Alas…Such is Life.